- Home

- Amie Kaufman

Battle Born Page 12

Battle Born Read online

Page 12

“The wind arches at the harbor,” Anders said, remembering. “They kept letting in huge gusts.”

“And lots of other small things besides,” Lisabet agreed.

“Well,” said Ellukka, “I hope Hayn likes the dragonsmiths as much as Leif does.”

“We’ll have to sleep here tonight,” Lisabet said. “We’d have to fly to pick him up, and then fly to the caves, and he’s going to be heavy. We’re meeting him at the town camp tomorrow morning anyway. I know Leif said it was urgent, but it’s too far and too dangerous to fly.”

So they slept at Old Drekhelm, all four of them piling onto Drifa’s bed. As Anders nestled his head down onto the pillow, he couldn’t help but think that once, his mother had lain in this very place. Like being in her workshop, her bed brought with it a feeling of closeness. He wondered where she had slept when she hid at Drekhelm, and tried to imagine her lying in bed with her babies sleeping nearby.

She must have been aching with sadness for their father, who had been killed, and afraid that she would be found and blamed for something she hadn’t done. She must have been afraid for Anders and Rayna as well. It must have been lonely.

Though neither he nor Rayna doubted their mother’s innocence, now that he lay here in the dark, he couldn’t believe he hadn’t thought to ask her if she knew who had killed Felix when he’d had the chance. And now she was gone.

That thought brought with it a sadness that stayed with him late into the night.

Chapter Eleven

THE NEXT MORNING, ELLUKKA AND LISABET LEFT for the town camp to meet up with Hayn, promising to bring him to the hermits’ caves as soon as they could. Anders and Rayna set off to find Tilda’s and Kaleb’s aerie.

They flew first over the Uplands, soaring above the broad, golden plains, watching the thousand streams that twisted and turned across them, mirroring the sky. Slowly, the perfect green carpet of the plains was broken up by small rocks, then large, and then they came to the foot of the Seacliff Mountains.

Rayna flew south of the Skylake, where they had found a piece of the Sun Scepter, wheeling through the passes that Hayn had shown them on the map, flying lower and more slowly, carefully hunting until they began to see the mouths of caves.

Then she dropped lower again, so the wind that was twisting its way through the peaks began to buffet her this way and that. It was hard going, and it was another half hour before they saw a large red flag outside a cave mouth, fluttering fiercely in the breeze.

Beside it was a broad, flat platform, perfect for landing, and as Leif had told them to, Rayna set herself down in the very center of it.

No sooner had her feet touched the ground than a series of mechanical fences sprang up from where they had been concealed, forming a perfect circle around the landing pad. At first, they were perhaps six feet tall, and Rayna made as if to take off again and free herself from their enclosure. Then another layer of fencing seemed to unfold from the top of the first, and another from the top of that, expanding until, within seconds, the twins were enclosed in a large dome made of latticed metal.

Anders slowly slid down Rayna’s side, putting down the package that contained the mirror, and then laying the staff on the ground beside it before he turned to pull off his sister’s harness. There didn’t seem much point in leaving it on when they clearly weren’t going anywhere.

“What kind of welcome do they call this?” she demanded as soon as she was in human form. “I don’t know about this place, Anders. There has to be another dragonsmith somewhere.”

“Not one that will listen to us,” he pointed out quietly.

Then a voice called to them from outside the fence. “Is that a harness? It looks very well designed. I like the strap that goes between your forelegs.”

There was a woman standing and looking in at them. She had a large shock of curly silver hair and a long, square-jawed face, suntanned from being outside.

“Yes, it is,” Anders called. “Can we come out, please?”

She considered this, tilting her head this way and that, studying them the way Isabina studied things through her microscope. “Who told you how to find us?” she asked.

“Leif,” he replied.

Her rather stern face lit up. “Oh, Leif,” she said. “Barely anyone else visits us. I suppose I should have known it was him.” She hurried around the dome and pulled open a gate using a latch on the outside. “Leif sends us supplies. I don’t suppose you have any for us?”

“Afraid not,” said Rayna. “He sent us because we need a repair.”

“Oh, a repair!” If anything, she seemed even more excited about this. “Nobody asks for those anymore. Come inside, come inside.” She raised her voice to a shout. “Kaleb, we have visitors. They need a repair!”

Anders couldn’t help wondering, as he followed her in, whether the reason nobody ever came to see them for a repair was that nobody knew where to find them. But he kept his mouth shut.

Kaleb turned out to be an old man with very dark-brown skin and hair just as silver as Tilda’s, cropped close to his head. His face was lined and wrinkled, and his expression gave nothing away as he looked them up and down.

“They’re children,” he pointed out, pressing a button in the wall near the cave’s entrance.

With a series of clanks, the dome and fence folded back down into place, the gray of the metal disappearing against the rock once more.

“Leif sent them,” Tilda told him, as though this excused their age.

“Well, what do you want?” he demanded.

“I’m sure they want food. Guests, Kaleb, we never have guests. We should feed them.”

Kaleb made a dismissive noise, waving away her words with one hand. But despite the gesture, he stomped over to a cupboard against the wall, opening it to remove four plates and one of the most magnificent cakes that Anders had ever seen. It looked to have at least a dozen thin layers, and between each of them was a thick layer of jam.

“Wow,” said Anders, who had not been expecting something that fancy to emerge from so plain a cupboard in the middle of the mountains.

“Kaleb made it,” said Tilda proudly. “We have a lot of free time up here.”

“Not enough else to do,” Kaleb said crankily. “Now. Tell us what you want.”

“This is the Staff of Reya,” Anders said, holding it up. “And inside this cloth is the Mirror of Hekla, though last time we opened it up and looked into it, we all ended up . . .”

“Seeing everyone as yourself,” Tilda finished for him. She and Kaleb had both gone quite still. “Where did you get these?” she asked.

“They used to be Drifa’s,” Anders hedged.

“Yes,” said Kaleb pointedly, “we know that.”

“Have you been stealing her things?” Tilda asked, all hints of friendliness now gone from her face. “How did you find these?”

“We used a map,” said Rayna quickly, eager to defend them. “We . . .” She fell silent, and Anders knew she had suddenly realized that if these dragonsmiths knew how Drifa’s map worked, then they would know that the twins were related to Drifa.

“No . . . ,” said Tilda.

“It can’t be . . . ,” said Kaleb.

He put down the cake and stomped in closer. Both he and Tilda took a long, long look at each of the children’s faces.

“And who is your father?” Tilda asked.

Anders knew this was where the greatest risk lay. But he wouldn’t lie and trick them into helping. They were doing all this to try to convince the wolves and dragons and humans to tell each other the truth, and to listen, so he had to start as he meant to go on. He remembered again that he had seen Tilda’s and Kaleb’s names in the Skraboks—they had probably known both his parents.

“Our father was Felix,” Anders said. “He was a wolf. And so am I.”

Tilda brought one hand up to cover her mouth. “Oh, Felix,” she said.

“We used to work with him and his brother,” Kaleb said. “Good

men.”

“I never understood what happened,” Tilda said. “They said that she killed Felix, and then ran. But the dragons hunted high up and low down, and they never could find her. I always wondered if whoever got Felix found her as well.”

Anders and Rayna exchanged a long glance—they both wished they knew the same thing.

“Well,” said Kaleb grimly. “If they did, looks like she got away for at least a little while, seeing as how you two are standing here in front of us. Protecting her babies would be a good enough reason to hide.”

There was something about the way he spoke—gruff, but just a little careful—that made Anders wonder if Kaleb and Tilda knew that Drifa had kept a forbidden workshop at Cloudhaven, a place nobody dreamed she would go, so nobody thought to look.

If the two dragonsmiths had suspected, obviously they’d never shared that suspicion with anyone, and that made them allies.

Kaleb appeared to be finished with the subject, and he cut himself a slice of cake, biting into it with a vehemence that didn’t invite questions. “These days, all we can do is forge,” he continued. “We need a designer. These foolish battles got in the way of it. There hasn’t been a new artifact in Vallen in ten years. Ten years! Do any of them think this was how it was supposed to be?”

“Well, um, good news,” said Rayna. “Felix’s brother, Hayn, is on his way. So you’ll have a designer very soon.”

“That’s wonderful!” said Tilda.

“It’s about time,” said Kaleb.

“You two sit down and eat your cake,” said Tilda. “We’ll work out how to repair your artifacts when Hayn comes.”

And so Anders and Rayna were both installed on a large, comfortable couch covered in a rug that didn’t really stop the stuffing coming out of all the holes in it. They each obediently ate a large slice of cake, and sat quietly as the dragons returned to their forging.

Watching Tilda and Kaleb work was like watching a beautiful kind of dance. Tilda transformed effortlessly into a peach-and-gold dragon with wings like the sunset coming through the clouds, breathing dragonsfire infused with essence into her forge, golden sparks leaping from the white flames. Then she slipped back into human form and picked up a hammer, setting to work beating her metal out flat. Over and over, she repeated the steps, never faltering.

Kaleb was engraving a metal plate that he was working on. He had a very old, very battered chart pinned up on the wall, and he would consult it, carefully studying the runes, then engrave another of them before returning to the chart once more. The paper was singed around the edges and had clearly seen many years of use. It must have been designed before the last great battle.

Anders was entranced, and except that his cake had disappeared, he would have had no idea how much time had passed.

Then, outside, they heard a series of metal clangs as the dome snapped into place once more.

A moment later, they heard Hayn’s voice shouting, half irritated, half amused. “Tilda? Kaleb? Let us out of this ridiculous contraption this minute!”

“Oh good,” said Kaleb, setting down his tools and turning for the door. “Now we can get to work.”

The twins followed the two dragonsmiths outside to find Hayn, Lisabet, and Ellukka trapped within the metallic dome, the two children looking much more concerned than the big wolf.

“Where have you been all this time?” Kaleb demanded as he stomped over to release the gate.

“You do know I can’t fly?” Hayn asked, a smile playing across his lips as the enclosure folded itself down to disappear into the ground again. “How, exactly, did you expect me to get up a mountain? You could have come to fetch me, if you wanted me so badly.”

Kaleb made a grunting noise and turned back inside. Hayn and Tilda exchanged a quick smile.

“I have more cake,” said Tilda, “and there’s milk somewhere as well. Let’s get you children settled. This might take a while.”

“It can’t take too long,” Hayn said gravely. “Things are getting worse.”

Anders thought of the Dragonmeet getting ready to launch an attack. Did Hayn know? “Worse?” he asked, dreading the answer.

“I’ve been keeping an eye on the wolf camp,” Hayn replied. “A group of them went to speak to the humans, and the humans drove them out. With rocks, with sticks, with anything they could lay their hands on.”

“Did the wolves fight back?” Lisabet whispered.

Hayn shook his head, but his expression was grim. “Not this time,” he said. “Every wolf is taught never to harm a human. But a human’s never harmed a wolf before. There’s talk around the human camp that they need to be ready for a wolf assault, and there’s talk around the wolf camp that they need to show up in force, to bring the humans into line.”

“Do you think they’ll do it?” Tilda asked, looking pale.

“I think all it takes is one human or wolf to begin it, and after that, I don’t know who’ll end it, or how,” Hayn replied.

Everyone was silent, and Anders closed his eyes. It felt like all of Vallen was on a collision course—the dragons readying themselves to attack the wolves, the wolves and the humans preparing to fight each other.

“We don’t have much time,” he said.

“Not much at all,” Hayn replied. “Tilda, Kaleb, we should get to work.”

Anders, Rayna, Lisabet, and Ellukka squashed onto the couch together, and Tilda loaded them up with big glasses of milk and even bigger slices of cake. In whispers, they caught each other up on what had happened since they separated, and then slowly fell silent as they watched the designer and the dragonsmiths work together. It was the first time it had happened anywhere in Vallen in over a decade, and Anders found he was holding his breath as they quietly talked over each of the artifacts.

Tilda had been right. No matter how urgent the work, it did take a long time—they studied, they debated, and slowly but surely, they settled on the repairs they wished to make.

It wasn’t just a case of re-engraving old runes. Hayn had to understand where and why the artifacts had begun to wear out, and create new combinations of runes that would reinforce them. The dragons would then need to forge the runes into place, taking care that each one was located exactly where it was required.

Some hours later, Anders was woken by Hayn, who was crouching in front of him and gently touching his knee.

“We’re ready,” the big wolf said, adjusting his glasses as he studied both Anders and Rayna, who was still waking up.

“Do you understand how these work?” Tilda asked from behind him. “They’re powerful.”

“We looked in the mirror last time, and it worked,” Rayna said.

“You won’t need to look in it this time,” Tilda replied. “Keep it wrapped up, and when you’re ready to use it, just unwrap it. Anyone who’s within, say, fifty feet of it, maybe more, will feel its effects. What about the staff? Do you know how to use that?”

The children all shook their heads.

“What are you doing,” grumbled Kaleb, “gallivanting around Vallen with artifacts you don’t know how to use? What Drifa would have had to say about that, I don’t know.”

Hayn snorted. “Drifa and Felix and I were always creating artifacts out of nothing. Half the time, we had no idea what they were going to do until they did it. I think Drifa would say that her blood runs strong in these two.”

The children all exchanged a long glance, but they kept quiet. It wasn’t the time to tell the dragonsmiths that Drifa had told them where to find the mirror and the staff. That would raise far more questions than it answered, and they had to focus on using them to try to start peace talks, before their time ran out. Thankfully, neither of them had thought to ask how Anders had known which artifacts to ask the map to show him.

Hayn pointed at the staff. “When you’re ready to use this one, take the end of it and drag it along the ground until you’ve drawn a circle. It doesn’t matter whether you can see the circle. You can draw it over rock, over

grass, anything you like. Anyone who steps inside it, their elemental powers will be completely neutralized. They won’t be able to breathe flame or cast ice. They won’t be able to transform.”

“At all?” Ellukka asked. “They’ll be humans?”

“Might do some of them good,” Tilda said.

Anders’s mind was racing. Already he could feel a plan beginning to form—he was starting to see what Drifa had thought of when he and Rayna had told her what they needed to do.

“Like I said,” growled Kaleb, “it’s powerful stuff. Are you sure you can handle it?”

“No,” said Anders honestly, “but we’ll try our best.”

“Good.” Kaleb gave him an approving nod. “That’s the first sensible thing you’ve said. If you know how hard it is to control, you’ve been paying attention.”

“We’d wait if we could,” Anders replied. “But we don’t have a choice. Hayn says the humans and the wolves could begin a battle any moment. And Leif said the dragons could attack by tomorrow.”

“He what?” Hayn said, pulling off his glasses and pinching the bridge of his nose. “How did you manage to see—no, that’s not the point. This is even worse than I knew.”

“This is why we live up in the mountains,” Tilda said. “This is how it was years ago, before your parents died. Only then it wasn’t the dragons trying to start something, it was the wolves making demands for repairs that nobody could meet.”

“They wanted to oversee our every move,” Kaleb agreed. “What happened to Drifa and Felix wasn’t the reason for all of it, it was the last straw. Sigrid was determined to have a fight.”

“Do you think she could be behind this now?” Lisabet asked, her voice so soft she was almost inaudible. Hayn shot her a pained look, and Anders slipped his hand into his friend’s and squeezed.

“I don’t know,” Tilda replied. “But I think that with or without the Fyrstulf, these dragons, wolves, and humans will find any excuse they can to start fighting one another.”

Unearthed

Unearthed Obsidio

Obsidio Gemina

Gemina Aurora Rising (ARC)

Aurora Rising (ARC) Memento

Memento Aurora Burning: The Aurora Cycle 2

Aurora Burning: The Aurora Cycle 2 Elementals: Battle Born

Elementals: Battle Born Aurora Rising

Aurora Rising Battle Born

Battle Born Undying

Undying Aurora Burning

Aurora Burning Scorch Dragons

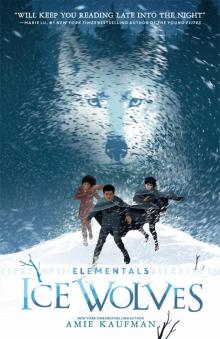

Scorch Dragons Ice Wolves

Ice Wolves Aurora Rising: The Aurora Cycle 1

Aurora Rising: The Aurora Cycle 1 This Shattered World

This Shattered World These Broken Stars

These Broken Stars Their Fractured Light: A Starbound Novel

Their Fractured Light: A Starbound Novel Their Fractured Light

Their Fractured Light Ice Wolves (Elementals, Book 1)

Ice Wolves (Elementals, Book 1)